This week we examine a scene from Pride and Prejudice that reveals Jane Austen’s great ability with dialogue, wit, and social observation.

All my content is free. So if you like what you find here, why not subscribe?

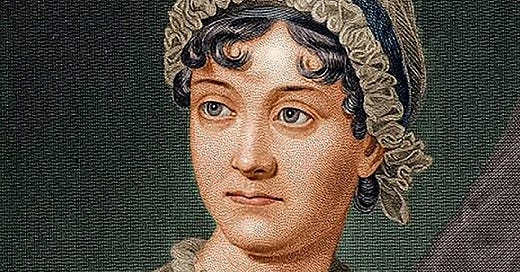

There is something very enjoyable in a typical Jane Austen scene: highly educated patter in and about elegant English estates, undercurrents of emotion, romance, and social aspiration. This has no doubt contributed to her continued popularity today, which certainly outpaces most literary authors, especially those who were writing over two hundred years ago. Today I’d like to analyze a fairly random excerpt from Pride and Prejudice that I think has much within it to learn from, and which demonstrates Austen’s particular strengths as a writer.

Context for the scene: Our hero Elizabeth is rather uncomfortably staying at the mansion of Mr. Bingley after her sister, Jane, fell ill during her visit there. Tormented by Mr. Bingley’s snobbish sister, and put off by the arrogance of Bingley’s guest, Mr. Darcy, she does her best to avoid the company of her hosts. But manners dictate she must appear now and then, so she finds herself drawn into the conversation that follows:

“I am astonished,” said Miss Bingley, “that my father should have left so small a collection of books. What a delightful library you have at Pemberley, Mr. Darcy!”

“It ought to be good,” he replied: “it has been the work of many generations.”

“And then you have added so much to it yourself—you are always buying books.”

“I cannot comprehend the neglect of a family library in such days as these.”

“Neglect! I am sure you neglect nothing that can add to the beauties of that noble place. Charles, when you build your house, I wish it may be half as delightful as Pemberley.”

“I wish it may.”

“But I would really advise you to make your purchase in that neighbourhood, and take Pemberley for a kind of model. There is not a finer county in England than Derbyshire.”

“With all my heart: I will buy Pemberley itself, if Darcy will sell it.”

“I am talking of possibilities, Charles.”

“Upon my word, Caroline, I should think it more possible to get Pemberley by purchase than by imitation.”

Elizabeth was so much caught by what passed, as to leave her very little attention for her book; and, soon laying it wholly aside, she drew near the card-table, and stationed herself between Mr. Bingley and his eldest sister, to observe the game.

“Is Miss Darcy much grown since the spring?” said Miss Bingley: “will she be as tall as I am?”

“I think she will. She is now about Miss Elizabeth Bennet’s height, or rather taller.”

“How I long to see her again! I never met with anybody who delighted me so much. Such a countenance, such manners, and so extremely accomplished for her age! Her performance on the pianoforte is exquisite.”

“It is amazing to me,” said Bingley, “how young ladies can have patience to be so very accomplished as they all are.”

“All young ladies accomplished! My dear Charles, what do you mean?”

“Yes, all of them, I think. They all paint tables, cover screens, and net purses. I scarcely know any one who cannot do all this; and I am sure I never heard a young lady spoken of for the first time, without being informed that she was very accomplished.”

“Your list of the common extent of accomplishments,” said Darcy, “has too much truth. The word is applied to many a woman who deserves it no otherwise than by netting a purse or covering a screen; but I am very far from agreeing with you in your estimation of ladies in general. I cannot boast of knowing more than half-a-dozen in the whole range of my acquaintance that are really accomplished.”

“Nor I, I am sure,” said Miss Bingley.

“Then,” observed Elizabeth, “you must comprehend a great deal in your idea of an accomplished woman.”

“Yes; I do comprehend a great deal in it.”

“Oh, certainly,” cried his faithful assistant, “no one can be really esteemed accomplished who does not greatly surpass what is usually met with. A woman must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages, to deserve the word; and, besides all this, she must possess a certain something in her air and manner of walking, the tone of her voice, her address and expressions, or the word will be but half deserved.”

“All this she must possess,” added Darcy; “and to all she must yet add something more substantial in the improvement of her mind by extensive reading.”

“I am no longer surprised at your knowing only six accomplished women. I rather wonder now at your knowing any.”

“Are you so severe upon your own sex as to doubt the possibility of all this?”

“I never saw such a woman. I never saw such capacity, and taste, and application, and elegance, as you describe, united.”

Mrs. Hurst and Miss Bingley both cried out against the injustice of her implied doubt, and were both protesting that they knew many women who answered this description, when Mr. Hurst called them to order, with bitter complaints of their inattention to what was going forward. As all conversation was thereby at an end, Elizabeth soon afterwards left the room.

“Eliza Bennet,” said Miss Bingley, when the door was closed on her, “is one of those young ladies who seek to recommend themselves to the other sex by undervaluing their own; and with many men, I daresay, it succeeds; but, in my opinion, it is a paltry device, a very mean art.”

“Undoubtedly,” replied Darcy, to whom this remark was chiefly addressed, “there is meanness in all the arts which ladies sometimes condescend to employ for captivation. Whatever bears affinity to cunning is despicable.”

Miss Bingley was not so entirely satisfied with this reply as to continue the subject.

This is almost the pure essence of the novel in one scene. At times the dialogue feels almost like fencing, as in the way Mr. Bingley wittily handles his sister harping on the greatness of Mr. Darcy’s estate, or how Mr. Darcy brushes off Miss Bingley’s attempt to undercut Elizabeth. Such moments are genuinely clever and memorable, and occur frequently in Austen’s dialogue. Quarrels over fairly serious matters, both material and ideological, are wrapped in and must be decided by weaponized politeness and higher manners.

Even in this small conversation you get a sense that all of the characters are real, developed people. Their concerns are believable and faithfully articulated; even despicable characters like Miss Bingley aren’t reduced a caricature, or a sounding board for the author to get out their opinion on the matter—a habit I think many writers fall into. Despite the fact that women’s accomplishments, as referred to here, and their broader place in society, were obviously important matters to Austen, the scene here plays out quite naturally.

The ideas touched on in this conversation are also emblematic of Austen: social ambition, as expressed in Miss Bingley’s covetous praise of Pemberley (and the subtext of her desire for Mr. Darcy), and the expectations of women. This scene, like much of Austen’s work, is an excellent blend of realism and social commentary. That is, the commentary emerges from a conversation that is utterly believable and grounded in realism—and on top of that, delightful to read.

Quite a lot is happening in this short scene. Beneath the charming wit of the surface-level dialogue, and besides the examination of standards applied to women, there is also the maneuvering and development of the characters. Miss Bingley especially, whose thirsting for Darcy and undermining of Elizabeth are practically ham-fisted. But also of Darcy, who seems to be pulled closer to Elizabeth here both by his expressed preference of women who engage in heavy reading, just as she has been avoiding conversation by reading, and his subtle but cutting rebuttal to Miss Bingley’s mudslinging. It might feel strange to call writing as ornate as Austen’s “economical,” but she does manage to cram quite a lot worth thinking about into two pages of what is almost purely dialogue.

That about wraps up this issue. Still struggling to maintain a constant schedule, but after this post I will try to keep them coming out steadily on Friday morning.

As always, hope you found something here that was worth your time.

—Floyd

All my content is free. So if you like what you find here, why not subscribe?

This button also does something I guess.

Just came across this post and really enjoyed it. I appreciated your comment about how these social concerns are very important to Austen, but "the scene here plays out quite naturally." That's very well said.

What sticks out to me in this passage is when Elizabeth makes her boldest claim, and others respond to her.

" 'I never saw such a woman. I never saw such capacity, and taste, and application, and elegance, as you describe, united.'

"Mrs. Hurst and Miss Bingley both cried out against the injustice of her implied doubt, and were both protesting that they knew many women who answered this description."

I think the passage naturally asks: does Elizabeth actually believe what she's saying? Is she suggesting that Darcy's standards are so ridiculously high as to be impossible? Or does she think the opposite, that Darcy is prejudiced (!) and ignorant, and she's trying to think of a way to disprove him?

I suppose it could be a bit of both, but I like thinking it's the latter. Elizabeth disagrees with Darcy--especially his claim, "I cannot boast of knowing more than half-a-dozen [women] in the whole range of my acquaintance that are really accomplished"--and she *could* say, "I can think of plenty of women who fit that description, named x, y, z, etc. etc." But instead, she does something much more clever, which is pretend to agree with Darcy, even heightening his argument, so that others leap forward to disagree with her (and therefore disprove Darcy). Darcy doesn't pick up on her stratagem, assuming instead that Elizabeth herself is prejudiced and kind of desperate. He doesn't understand, at least not yet, that he's been disproven (if one can accept that Mrs. Hurst and Miss Bingley's protests have merit).

The fact that Elizabeth leaves the room is very funny to me. She knows that everyone around her is too simple-minded to have understood what just happened, so she just exits, hoping they'll figure it out eventually. When Mrs. Hurst and Miss Bingley both say they know many women who disprove Darcy's belief, it's a kind of mic drop moment for Elizabeth, but the mic drop is happening only inside Elizabeth's mind. And, once the mic's been dropped, she bounces. Fun scene.

“Fencing” is the perfect word. I have been struggling to find one to describe her dialogue for a long time. There are no sword fights but we are often left with the adrenaline of an action scene!