Hemingway and the Development of Style

All my content is free. So if you like what you find here, why not subscribe?

The mark of any great writer is that given just a page of their writing, or even less, you can be sure they were the one to write it—that they were the only one who could have written it. This is a test that Hemingway certainly passes, and with flying colors.

It’s important to stop and appreciate what a difficult test this is. People have been writing in the English language for over a thousand years, and in our age of information overload millions of books are published every year. This says nothing of the terrifying volume of words spewed into the internet in the same span of time. But among the millions who have sent their writing into the world, in one form or another, to write something intelligible and consistently pass the test I describe is a feat only a handful of writers have achieved. They are all great writers, and I believe they would also all be called stylists.

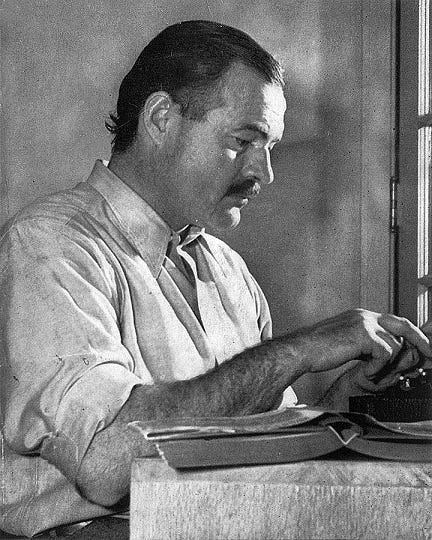

A stylist here means a writer with a distinct, developed, refined style of prose. Their writing is recognizable and unique on a word-by-word, sentence-by-sentence level. The great stylists have influenced English writing in its entirety, something also certainly true of our boy Ernie H, whose extraordinarily terse and minimalist style is inseparable from our idea of modern writing. So much bog-standard writing advice today which emphasizes simplification could equally be read as a guide for producing prose in the style of Hemingway. Amazingly, despite this, the difference between crisp, modern writing and Hemingway’s work is still easily discernible.

Here’s a fairly random sample from The Sun Also Rises:

The taxi went up the hill, passed the lighted square, then on into the dark, still climbing, then levelled out onto a dark street behind St. Etienne du Mont, went smoothly down the asphalt, passed the trees and the standing bus at the Place de la Contrescarpe, then turned onto the cobbles of the Rue Mouffetard. There were lighted bars and late open shops on each side of the street. We were sitting apart and we jolted close together going down the old street. Brett’s hat was off. Her head was back. I saw her face in the lights from the open shops, then it was dark, then I saw her face clearly as we came out on the Avenue des Gobelins. The street was torn up and men were working on the car-tracks by the light of acetylene flares. Brett’s face was white and the long line of her neck showed in the bright light of the flares. The street was dark again and I kissed her. Our lips were tight together and then she turned away and pressed against the corner of the seat, as far away as she could get. Her head was down.

You simply don’t need more to recognize it’s Hemingway. It’s so Hemingway. But how does he do it? I think it is all the little ways he breaks from the ordinary rules of modern writing that make him so distinct. In the first place: repetition. Probably the first thing any editor wants to cut, and any circulating Rules of Writing would implore you to cut, is repetitive words. In the hands of an amateur, repetition in writing appears clumsy and unpracticed. But Hemingway is a master of using repetition to elevate his writing into something extraordinary: the number of times “light” and “dark” and their variations appear in the excerpt above, for example. It only works because of how controlled his style is, so that the result isn’t messy, but almost hypnotic and surreal. His use of quite long, almost run-on sentences like the first one above also contributes to this effect, along with the signature way he mixes in such choppy sentences (Brett’s hat was off. Her head was back.) with the longer ones.

In this case the repetition is elevated further by symbolism: The flickering between light and dark as the pair rides along evokes the extremely on-again off-again nature of the narrator’s relationship with Brett. The connection is strengthened as the light is described as falling on and off of Brett’s face, and the light changing just as Jake kisses her and is rebuffed. Hemingway is also a master of subtext, you see, or what he called Iceberg Theory. The idea is, like an iceberg, only 10% of the story is above the surface. The rest is revealed through subtext and symbolism, inviting deeper reading to understand its full meaning.

I would like to point out that this is quite discordant with a major pillar of most commonly-circulated writing advice today, which is to maximize clarity for the most frictionless possible communication. Certainly it would be clearer for Hemingway to tell you what the flickering light means, or eschew the metaphor altogether. The problem is it would be artless. Of course, this advice was probably written with journalism or business in mind, not literary novels; I understand that and most of you probably do too. But that doesn’t stop rules like that from being paraded around the internet as though they were the Ten Commandments of writing, totally unbreakable and applicable to everything. I wish I could tell you I haven’t seen such rules used as critical bedrock to argue that any kind of subtlety or ornament in a work of literature was proof of its failure as a piece of writing. I wish I could say I haven’t seen it many times. But I’d be lying. Anyhow I’m sorry to rant, but that one’s been stewing a long time. Now where were we?

To round off my analysis of the excerpt above, I’d like to point out how understated yet potent the long line of her neck is here. In a vacuum it’s unremarkable, but with Hemingway’s setup it’s striking. The pair are jolted close together by the car. A sexual tension is created. As Jake watches Brett’s face come in and out of view, it’s like we’re catching those short glimpses of her. Then, suddenly, like Jake, we catch this detail: Brett’s face was white and the long line of her neck showed in the bright light of the flares. Without having to be told, we feel how he suddenly senses her beauty, and overcome with attraction he kisses her. The tension, the longing, the spark and the disappointment are all delivered in such a small space, and without ever having to tell us what Jake is feeling.

I have a special soft spot for Hemingway. I was assigned him in high school English class by pure chance, out of a list of many authors. He was maybe the first “serious” author I read, and certainly the first author I read seriously. His work made me acutely aware of prose for the first time, and what it could do, and since then I have always had a fascination with it. For this reason alone I will always recommend Hemingway to anyone who’s interested in the craft of writing (not that he needs my endorsement).

Anyhow, I’ll leave you here. My writing schedule was a little derailed by the holidays. Hope I’ve written something worth your time, and Merry Christmas.

— Floyd

All my content is free. So if you like what you find here, why not subscribe?